|

| Find the human! Pretty easy, right? RIGHT?? |

It is obvious what is "human" and what is not if we just look at living organisms. There's a clear gap between us and our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees. No danger of mistaking one for the other.

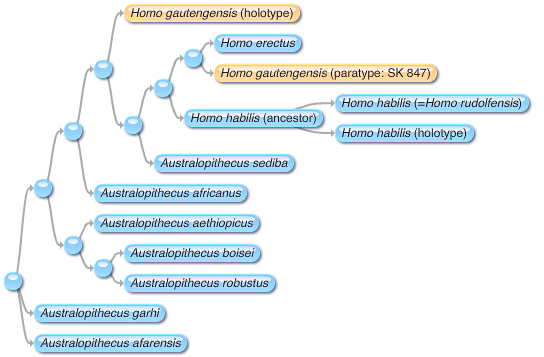

But this clarity vanishes as soon as we look at the fossil record. There's a gradient of forms between us and things that are not clearly closer to us or chimpanzees (

Ardipithecus,

Orrorin,

Sahelanthropus). Which ones are "human" and which are not? Is

Praeanthropus afarensis human? What about

Homo habilis?

Homo ergaster? Neandertals?

Homo sapiens idaltu?

|

Find the human! Or is there more than one?

Or are they all human? |

This issue crops up for all kinds of taxa. Much time has been spent arguing what is and is not e.g., avian, or mammalian. The issue is more common within vertebrates than many other taxa, since vertebrates have an especially good and well-studied fossil record. But it applies, in theory or practice, to every extant taxon.

I subscribe to the school of thought that names born from neontology (the study of extant organisms) are best restricted to the crown group (that is, to the living forms, their final common ancestor, and all descendants of that ancestor). Arguments for restricting common names to crown groups were first laid out by de Queiroz and Gauthier (1992). The primary reason for doing this is that it prevents unjustified inferences about stem groups (that is, the extinct taxa which are not part of the crown group, but are closer to it than to anything else extant). For example, we currently have no way of knowing whether the statement, "Within all mammalian species, mothers produce milk," is true if we include things like Docodon as mammals (or, as a few have done, even earlier things like Dimetrodon). However, if we restrict Mammalia to the last common ancestor of monotremes and therians (marsupials and placentals) and all descendants of that ancestor, then the statement unambiguously holds.

This system also gives us a very easy way to refer to any stem group: just add the prefix "stem-". Some examples:

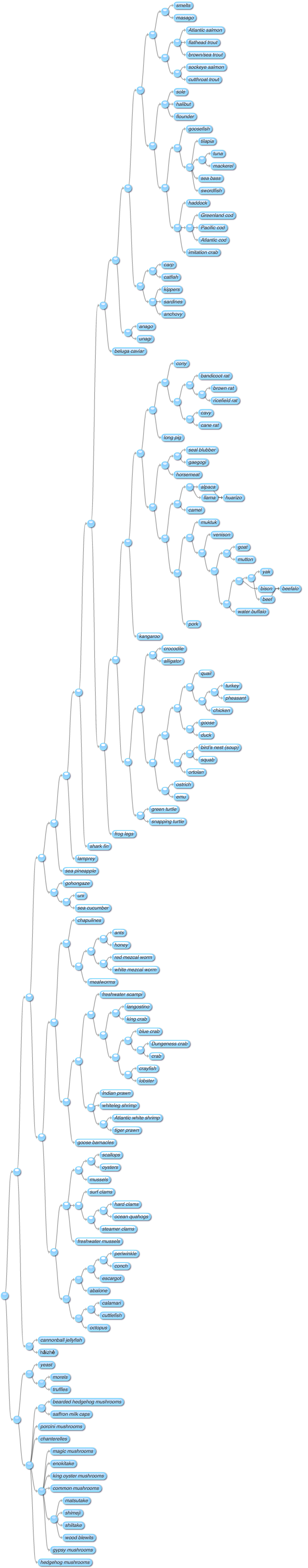

- stem-avians: Pterodactylus, Iguanodon, Diplodocus, Eoraptor, Coelophysis, Tyrannosaurus, Oviraptor, Velociraptor, Archaeopteryx, Ichthyornis

- stem-mammals: Casea, Dimetrodon, Moschops, Cynognathus, Docodon

- stem-whales: Indohyus, Ambulocetus, Pakicetus, Basilosaurus, Dorudon

- stem-humans: Ardipithecus(?), Praeanthropus, Australopithecus, Homo habilis, Homo ergaster

|

| stem-humans |

This is a nice, neat system. However, for humans, it gets a little sloppy the closer we get to the crown group.

For a long time, there was a debate in paleoanthropology as to how our species originated. We are distributed across the globe, so it's not immediately obvious where we are from. As the hominin fossil record gradually came to light during the 20th century, it became clearer that the earliest roots of the human total group were in Africa, since that's where the oldest remains are found. Everything before two million years ago is African, and only after that time period do we start to see remains in Eurasia, all of them belonging to the genus Homo. Remains in Australia and America don't occur until very late, and only modern humans appear in those regions.

But this leaves open the question of our own species' origin. Homo had spread all over the Old World by the time modern humans appeared, so we could have come from anywhere in Africa or Eurasia. Two major hypotheses were formed. The Out of Africa Hypothesis suggested that the ancestors of humans originated in Africa and then spread out over the globe, displacing all other populations of Homo: the Neandertals in West Eurasia, Peking Man in Asia, Java Man in Malaya, etc. The Multiregional Hypothesis, on the other hand, suggested that modern human races evolved more or less in their current areas: Negroids were descended from Rhodesian Man, Caucasoids from Neandertal Man, and Mongoloids from Peking Man.

These hypotheses competed with each other until the advent of genetic analysis. When scientists were finally able to study the mitochondrial genome, which is copied from mother to child, they found that all living humans shared a relatively recent matrilineal ancestor, much more recent than the splits between Rhodesian, Neandertal, and Peking fossils. Furthermore, the matrilineal family tree strongly points to an ancestor in Africa, where the most divergence is found. Study of the Y chromosome, which is copied from father to son, indicated an even more recent patrilineal ancestor, also African. The case seemed closed. Out of Africa had won.

The case seemed further bolstered when the Neandertal mitochondrial genome was recovered. It revealed a signature which clearly placed it outside the modern human group (Teschler-Nicola & al. 2006). Earlier this year, mitochondrial DNA was also retrieved from an indeterminate fossil from Denisova, Siberia, indicating that it represented a matrilineage even further out, preceding the human-Neandertal split (Krause & al. 2010).

This would give us a pretty nice, clean series of splits. And it would mean that Neandertals, Denisovans, etc. are stem-humans.

But there is more to ancestry than just the matrilineage and the patrilineage. Most of our ancestral lineages include members of both sexes (think of your mother's father and your father's mother). The matrilineage and patrilineage are the only ones that can be studied with clarity, since all other chromosomes undergo a shuffling process. But those other lineages exist nonetheless.

Only very recently has evidence come to light which challenges Out of Africa, at least in its strong form. Earlier this year, a study suggested that all humans except for Sub-Saharan Africans have inherited 1–4% of their DNA from Neandertal ancestors (Green & al. 2010). And just yesterday, a new analysis of Denisovan nuclear DNA showed that Melanesians have inherited 4–6% of their DNA from Denisovans. This nuclear DNA seems to originate from an ancestor close to the human-Neandertal split, but somewhat on the Neandertal side.

Long story short, the picture has gotten a lot more complicated. It's no longer, "Out of Africa, yes, Multiregional, no." Now it's, "Out of Africa, mostly; Multiregional, somewhat."

So what does this mean for the term "human"? Are Neandertals and Denisovans human? After all, they seem to be ancestral to some, but not all, modern human populations.

Well, they can only belong to the crown clade if they are the final common ancestor of all living humans, or descended from it. Neither of these criteria appear to hold. So, for now, I would still say that they are not human, only very close to human. (Note that this does not mean that people descended, in part, from Neandertals and/or Denisovans are somehow "less human" than those with pure African ancestry. The African ancestors are also not humans but stem-humans under this usage. This usage is discrete; you're either human or you aren't.)

Still, at this level of resolution, we start to see a problem with the crown clade usage. What is the final common ancestor? Many would assume it to be the last-occurring common ancestor, but this is problematic, and not just because that ancestor probably lived within recorded history (making, e.g., the Sumerians inhuman!). When I say "final" I'm really referring to something a bit more complex—the maximal members of a predecessor union. (More discussion here.) But determining what that is, exactly, requires better datasets than we have.

I still think it's a good convention, and if its application is a bit vague, so be it—our knowledge is a bit vague. For now I would say that humans are a clade of large, gracile hominins with high-vaulted crania that emerged roughly 150,000 years ago in Africa, and then spread out. They are descended from not one but at least three major populations of stem-human. One of these, the African population (idaltu, helmei, etc.), forms the majority of the ancestry, up to 100% in some populations. The others, Neandertals and Denisovans, only form a small part of the ancestry of some humans.

I feel this convention is useful because it prevent unjustified inferences. For example, we know that all living human populations have languages with highly complex grammar. We really don't know whether Neandertals and Denisovans had such languages, or whether the immediate African predecessors of humans did, for that matter. So it's good to be able to categorize them as stem-humans, because it reminds us that we don't have as much data available on them as we do for the crown group. We have to be more clever in figuring these things out.

And if we ever cloned a Neandertal? Well, ask me again once that happens.

References

- de Queiroz & Gauthier (1992). Phylogenetic taxonomy. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 23:449–480. [PDF]

- Green & al. (2010). A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science 328:710–722. doi:10.1126/science.1188021

- Krause & al. (2010). The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia. Nature 464(7290):894–897. doi:10.1038/nature08976

- Reich & al. (2010). Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Nature 468:1053–1060 doi:10.1038/nature09710

- Teschler-Nicola & al. (2006). No evidence of Neandertal mtDNA contribution to early modern humans. Pages 491–503 in Early Modern Humans at the Moravian Gate. Springer Vienna. doi:10.1007/978-3-211-49294-9_17